Recording a solo violin

This article discusses the challenges of capturing the violin's sound.

Bowed instruments are notoriously difficult to record. This is further amplified given that the price discrepancy between good and incredible instruments is upwards of a million US dollars. There are important differences between an intermediate-level classical guitar and a luthier-made classical guitar. Still, the tonal differences are either not too noticeable, or they can be corrected relatively easily by using different microphones or editing in the post. The tonal characters of violins are usually very different from one another. Minor adjustments to the instruments, such as the addition of fine tuners, can significantly alter its tone. Of course, the player's ability to produce the desired tone should not be overlooked either. Sometimes, players tend to exaggerate dynamics, especially when playing fortissimo, rather than focusing on the tone. It is important to note that today's microphones and preamplifiers carry enough oomph to capture every little detail. Players frequently change how they play on recordings compared to how they would have played if they were playing live.

Putting these aside, the actual recording process of a solo violin is just as complicated. It all starts with listening to the violin and the player in the room where the recording will take place. The recording engineer must walk around the instrument and listen to find the optimal location where the instrument's sound is sweet rather than harsh and brittle. Violins produce an incredible amount of overtones. Many of these harmonics need time to develop in the air. This is why the standard Decca recording tradition guides us to place microphones high up in the air. In many of the rooms we record, this is impossible. The following graphic is a simplified depiction of microphone placements for violins.

Only trial and error can reveal which position is the ideal position for each project. For example, placing the microphones a few feet up, facing the player (position A), can give a very natural "roomy" sound to the recording, but if the microphones are not high enough, or if the violin is too metallic sounding, the engineer might choose to place the microphones farther back, and in some cases even below the violin. This might sound counterintuitive as the body of the violin is the resonator, pushing sound away and up, but by placing the microphones lower, we can eliminate some of the harsh overtones while achieving a darker, smoother tone.

But the recording is only as good as the choice of microphones. We frequently get asked why we don't use our Schoeps microphones on many projects. Schoeps makes some of the most accurate microphones, revered by the classical music world. Their cost is justified by their ability to capture the sound as accurately as possible. When recording in a magnificent room, we tend to use these microphones to capture the sound as-is. On the other hand, when we are recording in a basement, attic, or living room on a busy street, we'd rather not capture the reality as-is. For this, we have collected a variety of microphones with unusual strengths and weaknesses.

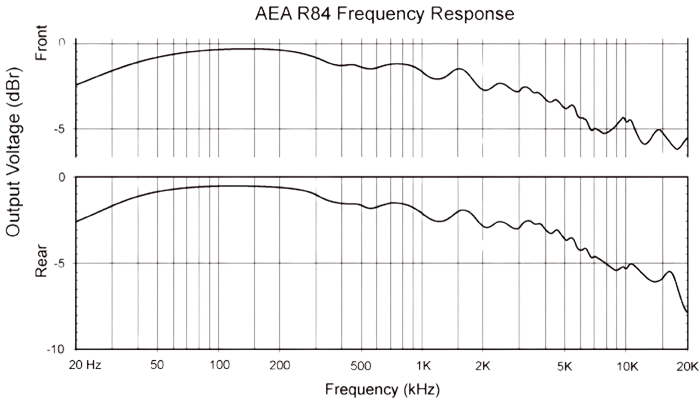

For example, ribbon microphones have a gentle roll-off on the higher frequencies, as shown in the following graph.

We really like using ribbon microphones on string instruments as their weakness in high-frequency sensitivity results in the rejection of those unwanted overtones generated by the instruments. The result is usually a much darker, sweeter tone. It is also possible to overshoot and capture too much bass. To avoid these, we frequently blend some small diaphragm condenser (SDC) microphones into the mix. SDCs, on the other hand, capture a ton of high-frequency content. By blending these two microphone types, we can achieve a very pleasant tone.

The differences between different makes and models of microphones matter a lot, too. Even the two of the same models of microphones can sound quite different. This is why we carry a lot of different microphones and utilize their strength as the project dictates.

We also advise our clients to re-string their instruments about a week before the recording session. This gives the strings just enough time to break in and perform at their best. If you haven't rehaired your bow in a while, maybe this is a good opportunity to schedule an appointment with the luthier.

Rocky Rhythms

Rocky Rhythms